Why should you read this report?

Deepfakes and biometric spoofing aren’t tomorrow’s threats. They are already undermining trust in core identity checks and biometric safeguards today. This report breaks down how attackers are bypassing facial recognition in banking apps and what real defenses actually work. Stay ahead of the next wave of identity fraud before it hits.

In this report, you'll learn about:

- The main attacks types on facial recognition systems

- Regulatory responses to attacks on biometric verification

- How the facial recognition process works

- Case studies containing original research on the three main attack levels

- Countermeasures to attacks including facial recognition SDKs and application shielding solutions

Read the report below or download below.

Quick links:

Facial recognition in the financial sector

Introduction

Welcome to our Q4 2025 App Threat Report, Promon’s quarterly analysis of current topics in mobile application security produced by our Security Research Team. We highlighted the growing threat of deepfake attacks in mobile banking earlier this year. Deepfakes are one vector for facial recognition bypass attacks. But the challenge of facial recognition security is wider than deepfakes alone and is acutely felt in the felt financial industry.

In our Q4 report, our team engaged with multiple banking customers to understand the key reasons behind attempts to bypass facial authentication systems. Analyzing attacks on facial recognition security in this sector required us to reverse-engineer some of the most common attack tools. This led us to classify different attack levels against facial recognition. While not neglecting others, our greatest focus was on application-level attacks, as they are the most prevalent.

Facial recognition in the financial sector

Facial recognition technology uses biometric algorithms to identify individuals by analyzing and mapping their unique facial features from images or video. Facial recognition is employed by service providers to verify user identity, enhance security, and streamline authentication processes.

Banks use facial recognition as part of their digital identity verification and fraud prevention strategies. An example of this is during a bank’s eKYC (electronic Know Your Customer) process, by which banks verify a customer’s identity electronically without the need for their physical presence. During enrolment, the user scans an ID card (typically with a government-issued ID photo, such as a driver’s license or passport) as well as their face. The system automates this comparison to check identity, confirm authenticity, and detect spoofing attempts (e.g., photos or deepfakes).

Main attack types

Attackers target or attempt to bypass facial authentication systems primarily to gain unauthorized access so they can exploit financial or personal data. In the banking sector, their motives might typically include:

- Financial gain

- Identity theft

- Data exploitation

- Circumventing security controls

- Regulatory or competitive manipulation

There are three main attacks methods. The first is creating a bank account in someone else's name.

The second attack method involves accessing someone’s existing bank account. Facial recognition acts as an additional authentication factor. So, in this case, the attacker not only needs to steal someone’s credentials but also their ‘face’ i.e. a convincing electronic spoof or mimic of their facial identity.

Thirdly, there also seems to be account sharing cases where people share access to their bank account for money laundering purposes. In this case, attackers also need authentication capabilities. The advantage that attackers could have here is that the person selling access to their account could also pre-record videos of themselves, alleviating the attackers from the need to create deepfakes.

Regulatory response

Regulators have already grasped the problem of attacks on biometric verification systems, like facial recognition. Some of Promon's of customers have received questions about their capabilities to protect against such attacks. One example of such a regulator is the is HKMA (Hong Kong Monetary Authority), Hong Kong’s banking regulator and central banking authority. The HKMA is increasingly focused on biometric and face-recognition technologies as part of its fintech and cyber risk agenda.

Read more: Financial App Security in 2025: Combating Traditional Malware and Emerging AI Threats

How facial recognition works

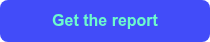

On both iOS and Android, there are two methods to process facial recognition.

Using the system’s biometry service

The first method uses the system’s biometry service. In this case, this authentication happens at the hardware level. Apps can either query the service to get a yes/no authentication result or perform cryptographic operations directly in secure hardware that are unlocked only upon successful biometric verification.

There is a huge advantage to performing authentication and processing in hardware because software attacks will not always be possible. That’s why relying on a yes/no answer is a weak way of utilizing this method, as that answer can easily be manipulated, whereas a cryptographic operation cannot.

The downside with using the system’s biometry service is that it is only possible to determine if the owner of the device is the one using it at that moment. There is no flexibility in the system to identify who that owner’s identity is in fact. This means it is not well suited for eKYC processes.

Using a facial recognition SDK

The other methods of processing facial recognition is by using a facial recognition SDK (Software Development Kit) that is embedded into the app. This works differently in that the SDK analyzes the camera feed and performs the user identification there. This is usually what is used for eKYC as the SDK can do whatever is necessary to analyze the camera feed.

The downside of this approach is that all user identification/authentication occurs in software. The camera feed passes through numerous software processes before it is analyzed by the SDK. This creates many different possible points where the system can be attacked.

These kinds of systems also have different ways to analyze the camera feed. It is possible to perform these analyses completely locally to the device. This has privacy and availability benefits. But the efficacy of these benefits depends on the processing power that is available on the local device. If the model is local, it is relatively easier to analyze in comparison to a server-located model.

On the other hand, all processing could happen in the cloud. This has the benefit of superior processing power. In practice, a hybrid model is often used where some simple validation happens locally, and more extensive checking happens on the server if the simple validation passes.

Facial recognition process

Facial recognition is typically divided into two separate validation steps. First, the system checks if the camera feed looks like it is a live video. This is called a liveness check or liveness detection. It is a is a security feature used in facial recognition systems to ensure that the face scanned belongs to a real, live person, as opposed to a photo, video, mask, or deepfake. Second, the person is identified.

Attacks on facial recognition

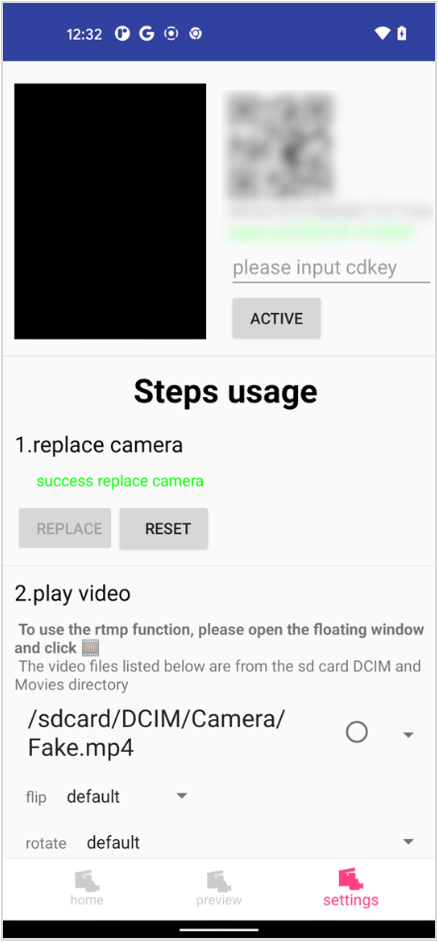

Attacks usually happen by replacing the original camera feed with a pre-recorded or on-demand generated video feed. In the case where the victim is not cooperating, this is often achieved by finding some image material of the victim. Then, a deepfake service is used to generate a realistic-looking video from it. If the victim is cooperating (e.g., as they do in the account sharing case), a real video could be used instead.

From this point, attacks tend to occur in two different ways. They replay a pre-recorded video and make it look like a real video feed. Or they stream a video from an RTMP (Real-Time Messaging Protocol) server. An RTMP server enables real-time video transmission, making it both a core streaming tool and, when abused, a vector for live deepfake or replay attacks.

It is important to note that attacks on facial recognition systems usually happen on the device of the attacker and not on the victim's device. This is advantageous for attackers because they control their device and can compromise it as they wish.

Attack analysis method

Our method of approach was to collect all the different tools that were available for applications and the systems that supported them. Then, we reverse engineered these tools to understand how they work. Finally, we categorized them based on the levels shown below.

- App level attacks: This is an attack that happens inside the sandbox of the app that is being manipulated.

- System level attacks: This is an attack on the system of a component through which the camera stream travels.

- Hardware level attacks: This is an attack where the camera feed is manipulated at the hardware level.

Our research of app level attacks and system level attacks was empirical, as it was conducted by direct observation and experimentation. Our research of hardware-based attacks was secondary, as we conducted it by analysis of existing data and studies.

App level attacks

Attacks on the application level need to be able to manipulate the camera feed through which the app sees. This typically happens by manipulating the API calls that receive the camera feed. There are two different ways to achieve this:

- Static attacks: These use repackaging of the target app

- Dynamic attacks: These use a hooking framework

An attacker would require a jailbroken or rooted device to be able to hook into an app. Or, on Android, the same kind of attack is possible using a virtual space app into which both the attack tool and the victim app are installed. This method bypasses sandboxing restrictions because both apps will run in the same sandbox and are therefore able to manipulate each other.

These kinds of attacks are easy for app shielding to detect because they happen inside the sandbox where the app shielding solution is located.

Cast study #1: Objection

For apps that only rely on a simple yes/no response from the system’s biometry service, attackers have an easier path. They can bypass authentication by hooking the code that processes that result, effectively forcing a ‘success’ outcome. This kind of bypass can often be achieved with minimal effort, for example by using a basic Frida script.

One example of a tool that performs this function in iOS is Objection. The open-source tool Objection is a runtime mobile application exploration toolkit built on top of Frida and maintained by SensePost. Objection has the ability to 'bypass' iOS biometrics such as FaceID as features. Since it is an open-source project, we were able to analyze it by checking the course code of the biometry bypass found here.

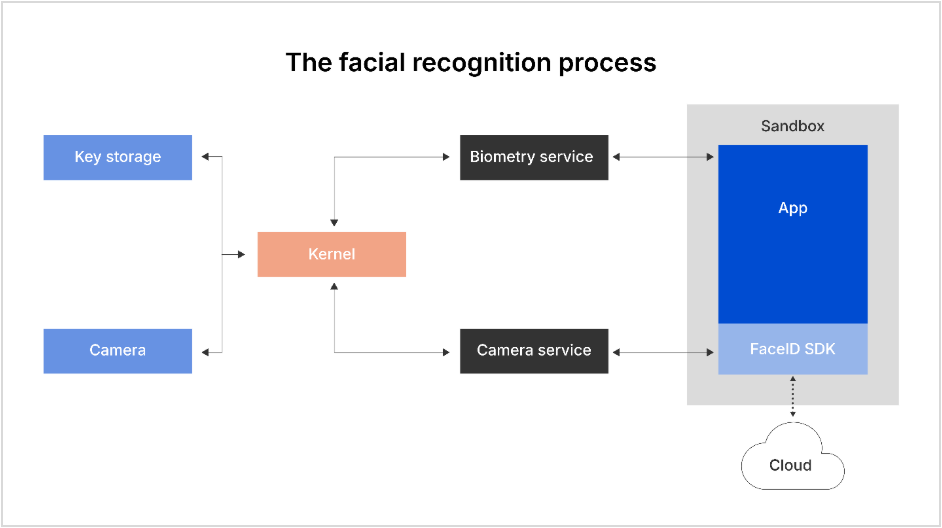

Case study #2: iOS-VCAM

iOS-VCAM is an open-source jailbreak tweak for iOS devices that allows the substitution of the real camera feed with a chosen image or video. This effectively creates a virtual camera on the device. The tool is intended to bypass facial recognition SDKs as opposed to manipulating simple yes/no answers from the system’s biometry service.

The paid tweak gets injected into the target app using Mobile Substrate or one of its forks/re-implementations. Tweaks rely on Mobile Substrate to hook and swizzle functions within Apple’s frameworks or within the app itself. By replacing or intercepting existing methods at runtime, a tweak can silently change how an app behaves without modifying the app’s code on disk.

In this attack, a malicious tweak is injected in an app's process on a compromised device. It hooks and swizzles several AVFoundation functions related to camera input and display, giving the attacker the ability to intercept or alter the video feed before it reached the app. This means the attacker could falsify or manipulate what appeared to be a live camera view.

The manipulation occurs entirely within the affected app’s runtime. It does not spread to other apps or the iOS system. And it is only possible on devices where security restrictions have been deliberately disabled.

Apple’s AVFoundation framework is responsible for how iOS apps access and manage camera and audio functions. It handles live video capture, still photography, and how those images are displayed on screen through components such as AVCaptureSession and as AVCapturePhotoOutput. Under normal circumstances, this framework operates securely inside each app’s isolated environment, ensuring that camera data cannot be tampered by outside code.

The analysis was performed statically using Ghidra. Since the relevant code that places the hooks was not obfuscated, no additional tools were needed.

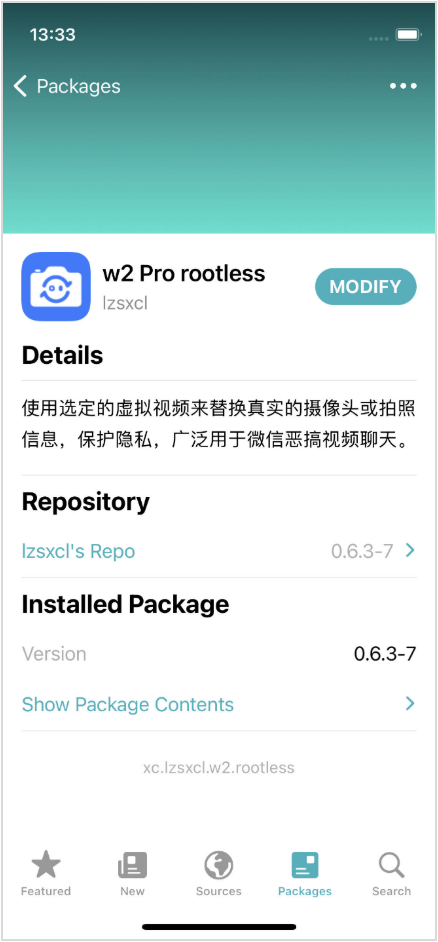

Case study #3: VCAM Android

On the Android side, there is a similar tool called VCAM that also allows manipulation of the video feed to bypass facial recognition SDKs. The tool is implemented as a Xposed/LSPosed module. This is a hooking framework that can hook Java code. The tool is based on virtual cam code.

It hooks common APIs that are used to access the camera feed and replaces it with a pre-recorded video. Being an Xposed/LSPosed module, the tool can either be used on a rooted device or installed together with the target app in a virtual space like Meta Wolf.

This LSPosed module is unobfuscated Java code only. So, for reverse engineering, we used the Jadx decompiler for analysis.

System level attacks

Another way to manipulate the camera feed is by targeting a specific system component that processes or handles the camera stream. This is typically achieved using either the hooking of a system component or by manipulated firmware. As opposed to app-based attacks, these based system attacks happen outside of the app’s sandbox and are therefore much more difficult to detect for an app shielding solution.

Case study #4: VCAMSX

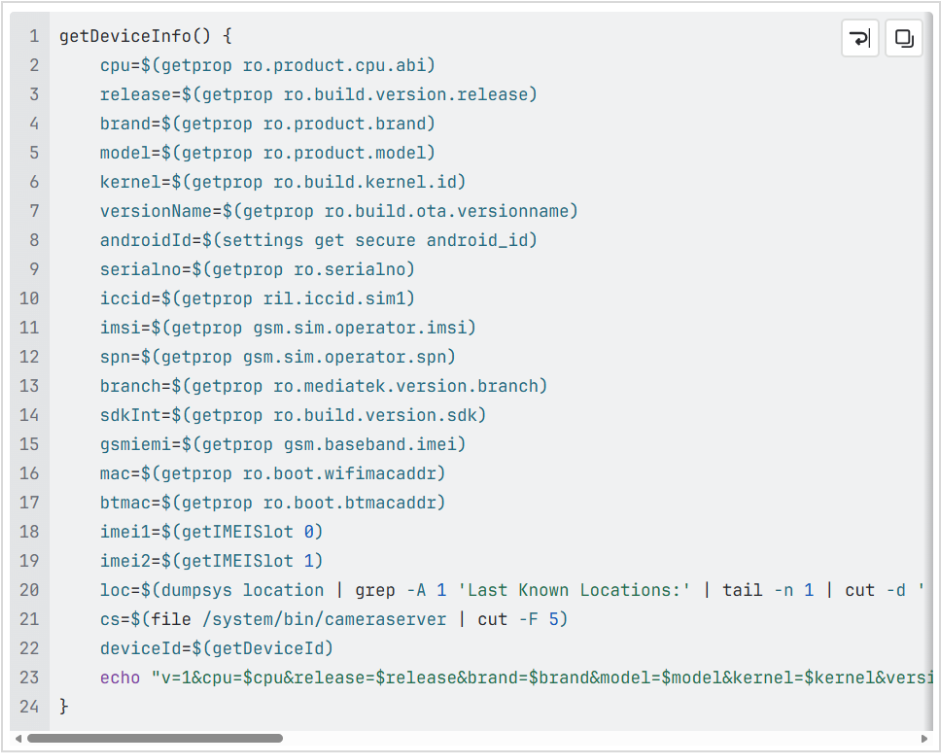

VCAMSX is a paid Android tool that requires root to manipulate the camera feed by means of manipulating a system component. VCAMSX works by using several assets at various stages.

- VCAMSX has an app that is used to control what it does. When this app wants to modify the camera feed, it launches one of its assets called assets/sh. This is a shell that can decrypt the script it is passed to.

- assets/chmp4.sh is passed to that shell. This is an encrypted shell script that the shell decrypts. This script can perform different actions.

- The most important uses a tool based on AndroidPtraceInject that injects a native library called assets/bin64/libhookProxy.so into the cameraserver daemon of the Android system. This daemon is responsible for providing the camera feed to apps.

- The assets/bin64/libhookProxy-1364.so library loads assets/bin64/libshadowhook-1364.so, which is the is ShadowHook hooking framework as well as assets/bin64/libCHMP4-1364.so.

- The assets/bin64/libCHMP4-1364.so library then places inline hooks into various functions in the libcameraservice.so library in cameraserver to be able to replace the real camera feed with a video that the user can choose via the VCAMSX app.

When analyzing the VCAMSX tool, we came to understand that the to encrypted shell script assets/chmp4.sh has functionality to collect much information about the device on which it runs, including the user’s location. This is an excerpt of that functionality.

The analysis of this tool presented us with more ofa challenge. The Java code of the app is obfuscated using nmmp. This extracts the Dex bytecode of Java methods and makes them native. When they get invoked, the bytecode gets executed in its own vm.

We used Frida to analyze that behavior. But the code we were most interested in was not in Java. We were mainly interested in the encrypted shell script assets/chmp4.sh that is invoked and decrypted by assets/sh.

To decrypt the script, we first analyzed assets/sh in IDA Pro. From this analysis, we understood that it is decrypting the shell script on the fly. Rather than statically reversing the decryption, we opted for the quicker way of using code emulation. We wrote a Qiling script that emulates the shell and dumps the script once it has been decrypted.

Another essential component of VCAMSX is the assets/bin64/libCHMP4-1364.so library that gets injected into cameraserver. We statically reversed most parts of it using IDA Pro. But some strings had string obfuscation applied. Instead of statically reversing these strings, we opted to use the gdb debugger. We wrote a small executable that loads the library and runs its initialization function. We then attached gdb to it and were able to extract the strings we needed.

Hardware level attacks

The last level where the camera feed can be manipulated is the is hardware level. Under certain conditions, the camera hardware can be exchanged with a device that plays back a pre-recorder video or a video stream.

A good example was shown at a BlackHat talk in 2019 called Biometric Authentication Under Threat: Liveness Detection Hacking.

This is the most complex attack. But it is also the most complex for an app shielding solution to detect because it has no direct access to the hardware.

Countermeasures

When it comes to the responsibility to detect such attacks, we believe a multi-layer approach is best. Both the facial recognition SDK and the app shielding solution need to add improved detections. These are the areas where facial recognition SDKs and app shielding solutions can help detect attacks.

Facial recognition SDKs

These are longer-term initiatives that banks and other financial institutions can take to secure their mobile apps against deepfake and other facial recognition threats.

- Advanced liveness detection: This is a defense layer that protects facial recognition systems from being tracked by static or synthetic replicas. Advanced liveness detection uses multi-layered signals and AI-driven analysis to detect whether a face exhibits natural, live behavior. Additionally, liveness detection can involve requiring the user to authenticate by performing different actions that make the use of pre-recorded videos more problematic, such as moving their phone or their head in a random direction. In financial apps, this protection is essential to prevent account takeovers, fraud, and unauthorized access.

- Detecting anomalies in video feed: This is the use of AI models and computer vision algorithms to identify irregular or suspicious patterns in a camera feed. It’s a real-time analysis layer that determines whether the video under analysis views like a genuine video feed. For example, if the device has a 10MP camera, but the video is in 20MG, this is evidence of manipulation. Facial recognition SDKs can check for such anomalies. In mobile banking, anomaly detection prevents biometric spoofing and supports liveness detection.

- Multi-sensor authentication: This is a layered biometric verification approach that combines data from multiple sensors, e.g., camera, microphone, even infrared (IR), depth sensor, and motion sensors. It’s designed to make it virtually impossible for attackers to spoof, replay, or synthetically generate biometric signals that can pass as legitimate.

Application shielding solutions

These are the main elements in application shielding that serve as security countermeasures to facial recognition attacks.

- Static and dynamic app integrity validation: These are two complementary mechanisms that are used to ensure that a banking app and its biometric authentication process, such as facial recognition, have not been compromised. App Shielding can validate whether the application has been modified either statically by patching it on disk or dynamically using tools like hooking frameworks to place hooks while the app is running. Strong protection in those areas will detect any kind of app level attacks.

- Detection of abnormal environment: This is the process of identifying whether the device, operating system, or app runtime environment has been compromised. It ensures that a banking or any other kind of app is running in a safe, authentic, and trusted environment before trusting what the camera or sensors are showing. While system level attacks happen outside of the sandbox of the app and are therefore hard for App Shielding to detect, checking the system for anomalies can indirectly detect such attacks.

Conclusion

Our research has concluded that Promon Shield for Mobile™ detects all the app level tools we found in both iOS and on Android. We detected these tools out of the box even before we knew such tools existed because we have strong runtime controls that cover the methods that these tools use. We did not detect the system level attacks yet, but we are working on integrating detections in the future.